Below-the-radar classics you need to read, by the editors who rediscovered them

Undeservedly overlooked books recommended by the editors who have brought them back to print.

From the Scottish novel that was shortlisted for the first ever Booker Prize then slipped into obscurity, to the forgotten memoir brought back to life thanks to a secondhand bookshop, here are some rediscovered gems for your TBR direct from the editors who found and republished them.

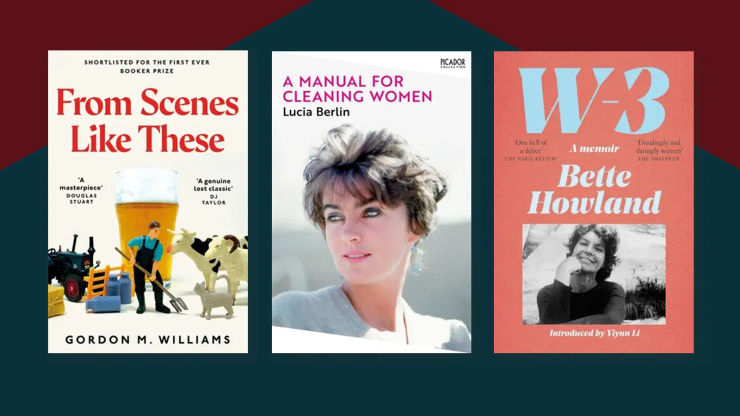

From Scenes Like These

by Gordon M. Williams

Rosie Shackles, Assistant Editor at Picador, says:

From Scenes Like These by Gordon M. Williams was first published in 1968, and was shortlisted for the inaugural Booker prize. Although Gordon M. Williams has some cult readers, the book went out of print, and despite critical acclaim, went on to be largely forgotten. I read it after it was recommended to me as a lost Scottish classic by Douglas Stuart, author of Shuggie Bain and Young Mungo. It quickly became apparent that this is a story that has retained all of its impact today.

From Scenes Like These is set in the west of Scotland in the 1950s. As part of the post-war boom, new houses are going up and factories are opening, but Dunky Logan, a fifteen-year-old from working-class Kilcaddie, has left school to work as a labourer on a local farm alongside so-called ‘real men’. It is a stirring social commentary well ahead of its time, and a brilliantly realised, devastating portrait of rural, post-war Scotland. We often speak about the lack of working-class literature. Here is a perfect example of a working-class novel that has, for many, slipped under the radar. I’m Scottish, and to be able to republish Williams for a new generation is extremely exciting.

W-3

by Bette Howland

Brigid Hughes, editor and publisher of the Brooklyn literary magazine A Public Space, says:

An editor is part sleuth, part subsonic listener, we search in all sorts of directions for writers and work. A few years ago, browsing in a secondhand bookstore in Manhattan, I came across a book on the one-dollar cart. W-3 by Bette Howland. I opened to a page at random:

'All I knew was this: I couldn’t take it anymore, no longer could bear this burden of concealment. Things seemed bad enough without adding extra weight. I wanted to be rid of it all, all of it. I wanted to abandon all this personal history – its darkness and secrecy, its private grievances, its well-licked sorrows and prides – to thrust it from me like a manhole cover. That’s what I had wanted all along, that’s what I was trying for when I swallowed those pills – what I hoped to obliterate. That was my real need. It had at last expressed itself, become all powerful.'

How could one not want to read on?

I love the way W-3 upends expectations for a memoir. The way Howland pays attention to the world of W-3 [the psychiatric ward she is on], the other patients, the doctors, the visitors. And how we come to know her through what she notices about others. Also, her joy and her superb humor.

A Manual for Cleaning Women

by Lucia Berlin

Lucia Berlin was relatively unknown during her lifetime, but eleven years after her death, forty-three of her short stories were selected for publication in A Manual for Cleaning Women. These semi-autobiographical tales of working-class people and their everyday lives – in the laundromat, in the ER, in schools, in other people’s houses – are as relevant and fresh as they were when they were written.

Stephen Emerson, editor of the collection, says:

Compiling the stories for this book has been a joy in countless ways. Black Sparrow and Lucia's earlier publishers gave her a good run, and certainly she's had one or two thousand dedicated readers. But that is far too few. The work will reward the most acute of readers, but there is nothing rarefied about it. On the contrary, it is inviting.

Lucia's writing has got snap. When I think of it, I sometimes imagine a master drummer in motion behind a large trap set, striking ambidextrously at an array of snares, tom-toms, and ride cymbals while working pedals with both feet. It isn't that the work is percussive, it's that there's so much going on. The prose claws its way off the page. It has vitality. It reveals.

More rediscovered and rescued classics

A Different Drummer

by William Melvin Kelley

In a similar way to Bette Howland, William Melvin Kelley owes his literary renaissance to a chance find in a thrift store. The New Yorker writer Kathryn Schulz bought a $1 hardback of a Langston Hughes book, which she discovered was dedicated to William Kelley, who she then researched and wrote a piece about in the magazine. A Different Drummer tells the story of a small Southern town where all the Black people have taken their possessions and left. Told from the perspectives of the remaining white people, it provides a striking viewpoint which considers the damage white supremacy does to all who live within its systems.

The Master and Margarita

by Mikhail Bulgakov

This book has caused waves since it was first published in the 1960s, though it was written earlier in the twentieth century in a Soviet Union under Stalin’s rule – and Mikhail Bulgakov actually burned the original version. Indeed, even the sixties edition didn't reflect the original text, having been heavily censored, and it was another seven years before the final manuscript was published in full. The action sees the Devil, disguised as a magician, arriving in 1930s Moscow on a mission. Surreal, satirical and surprising, it's the literary equivalent of pulling a rabbit out of a hat.

The Trial

by Franz Kafka

Unpublished in Franz Kafka’s lifetime, and almost not published at all, as the author requested the manuscript be destroyed, unread, this profound psychological horror teeters between reality and fantasy throughout. Kafka's friend Max Brod ignored the instructions to destroy the story, but the order of the chapters has been disputed and it ends rather abruptly as it was left unfinished. Somehow, though, this doesn't matter, and only heightens the labyrinthine nature of the novel. Just what crime did Josef K. commit? No-one can say, but he's going on trial for it. Or he would be, if anyone had given him the address of the courthouse.